Feature

Baltic Eagle: inside Estonia’s Ämari Air Base

Amid increasing tensions, Nato monitors Baltic airspace from Ämari Air Base. John Hill reports.

Main image: Italy is providing Baltic airspace policing as part of a Nato rotation. Credit: Erlend Štaub/Trade Estonia

Cover Story

Eye in the sky

As the first line of threat detection, airborne early warning is a must-have capability for the world’s militaries. Gordon Arthur reports.

Australia was the first country to adopt the E-7A Wedgetail. Credit: Gordon Arthur

Recent weeks have seen elevated tensions between the Nato Alliance and Russia, following the incursion of Russian fighters into Estonian airspace, combat drones over Poland, and Moscow’s continued assaults in Ukraine.

The confluence of diplomatic pressure continued at the United Nations in New York and the North Atlantic Council in Brussels, attempting to discern a way to prevent future Russian threats.

During a visit to Ämari Air Base some 23 miles outside of Tallinn in late-September, from which Italian aircraft responded to Russian intimidation across Central and Eastern Europe the same months, military officials walked Global Defence Technology through the details of the interceptions as well as new assets being used to secure the skies.

Italian personnel currently serve as the latest rotational contingent to conduct Nato Air Policing in the northerly Baltic nation. The strategic Estonian air base, which initially opened in 1945, originally supported elements of the Soviet Union’s Baltic Fleet in the early years of the communist regime of the Estonia SSR.

After the USSR’s collapse, the Estonian Defence Forces eventually housed an air force unit there in May 1997. There have been major construction works in that time to integrate the air base into Nato’s collective air defence system.

Fast forward to the beginning of September 2025 – the Italian Air Force, under the Baltic Eagle III mission, arrived to provide a Quick Reaction Alert (QRA) response while also delivering a tangible commitment to the defence of the airspace across their area of responsibility spanning the entire Baltic region.

During the visit on 24 September, this presence included F-35A Lightning IIs, Eurofighter Typhoons, a single E-550A Conformal Airborne Early Warning aircraft, and the SAMP/T air defence system.

The Task Force Air 32nd Wing, composed of personnel from the Italian Air Force and Army, assumed responsibility for Baltic airspace surveillance since 1 August 2025. This constitutes Italy’s third participation in the wider mission to Estonia, off the back of stints in 2018 and 2021.

The DroneGun Mk4 is a handheld countermeasure against uncrewed aerial systems. Credit: DroneShield

One key programme that will affect by a number of European operators is the evolution of the Type 212A conventional diesel-electric submarine (SSKs) design. Three nations are building on this legacy model in two different variations: first, the German and Norwegian Type 212 Common Design (CD) and second, Italy’s U212 Near Future Submarine (NFS).

It will also be valuable to examine how these changes differ from the capabilities offered by other European SSK designs, including the Dutch Orka class and Swedish Bleckinge-class submarines.

Nato interception

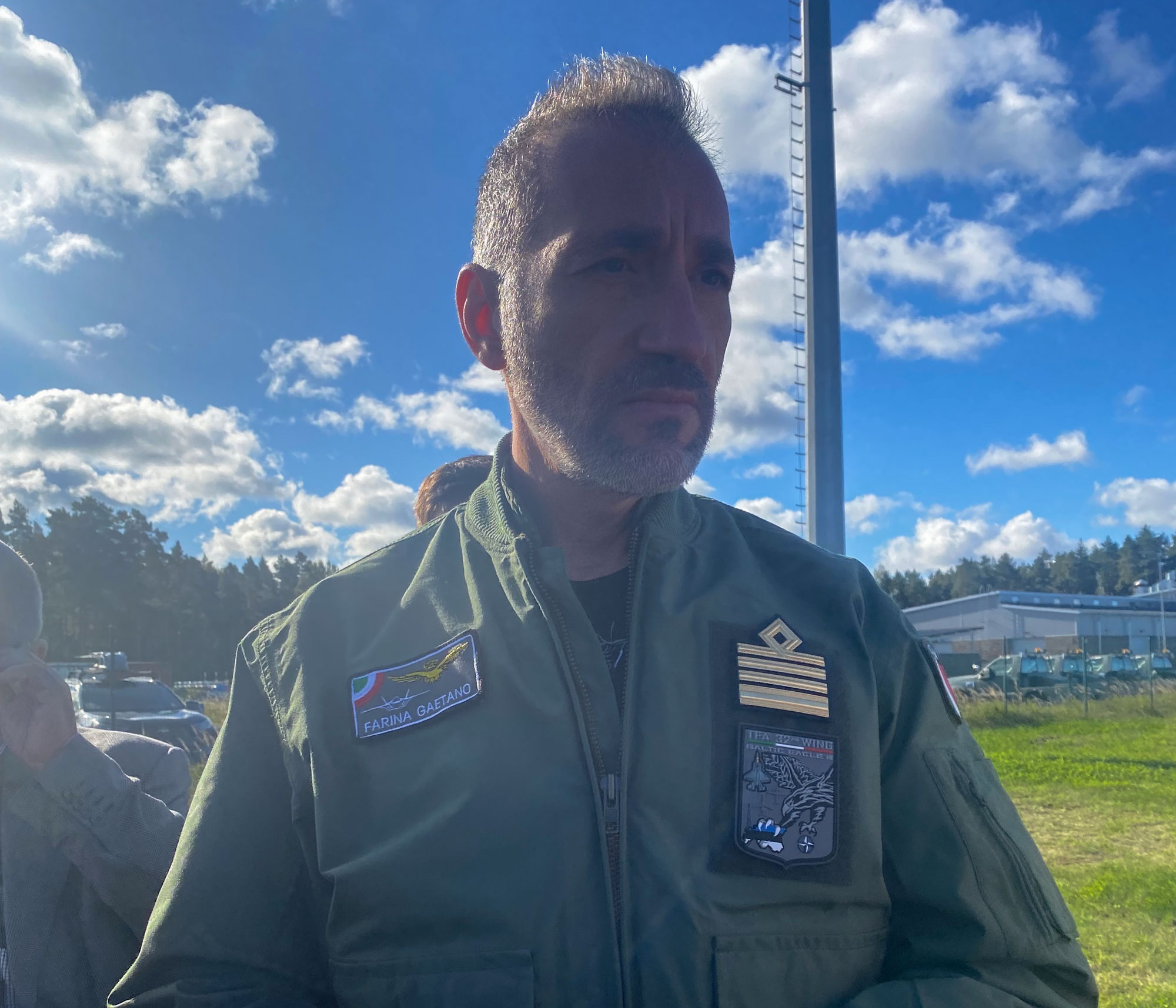

“It was a normal day like today,” said the Italian Task Force commander, Lt Col Gaetano Farina, who was in charge of the Nato Air Policing contingent at Ämari Air Base when two Italian F-35s scrambled to intercept three Russian MiG-31 fighter jets five nautical miles deep into Estonian airspace on 19 September, in what became an unprecedented 12-minute escapade.

“We got the indication that something is about to happen, we will have the information [from] the CRC [control and reporting centre] on the ground…They sent an alert… We received the alarm. So, the pilots, the crew, [were] here in QRA… in a few minutes we were able to take off and see what’s going on,” Farina described.

“Then after that we just escorted [the three Russian fighter jets] through to different planes, so they went through another [jet] from Sweden,” where they were then escorted to Kaliningrad, a Russian exclave sandwiched between Poland and Lithuania.

Lt Col Gaetano Farina, Italian Task Force Commander of Nato Air Policing contingent in Estonia. Credit: John Hill/GlobalData

Curiously, Farina emphasised that the Russian pilots behaved in a “professional” manner, despite the unlawful infringement of sovereign airspace and the fact that their transponders were turned off, meaning the trio were intentionally invisible to radar and Air Traffic Control.

The Russians responded in kind to the F-35’s wing rock, which is an international sign among pilots which indicates compliance during an interception. The Estonian Minister of Defence confirmed in a media briefing after the incident that there were no discernible weapons systems carried by the Russian jets.

However, responding to a question from Airforce Technology during the visit, Farina confirmed that the two F-35s were carrying air-to-air missiles for “self-defence”, but he was not at liberty to say what type they were. Nevertheless, Farina continued, “there was no escalation at all.”

CAEW aircraft

The Italian military is one of 17 countries that operate an airborne early warning and control aircraft.

Based on the Gulfstream G550 business jet, Italy’s CAEW platform – which can fly for eight hours at a time – provides airborne surveillance, command, control, and communications capabilities.

This constructs a 360-degree picture using four radar components for a detection range of around 200 nautical miles, as well as electronic intelligence and secure communications, crucial for battlefield information superiority.

A CAEW patrol aircraft at Ämari Air Base. Credit: John Hill/GlobalData

This came in handy in Nato’s QRA response on the night between 9-10 September, when 19 cases of incursion by drone-type objects entered Polish airspace, which are said to have been launched from the direction of Belarus and Russia.

An Italian Air Force official confirmed that the CAEW platform was already flying at the time the drones entered Polish airspace, undertaking a routine “scheduled task”.

Information soaked up by the Italian asset, which was said to have also entered Polish airspace from Estonia to support the allied response, was then shared with the command level, other aircraft, and units on the ground – all in real time.The aircraft was not operating alone, however, with multiple assets on the ground that were working at night. It was a shared job to detect and track the threats.

SAMP/T

As part of their tangible commitment to the region, Italy shipped the Franco-Italian SAMP/T medium-range air defence system to Ämari. The move forms part of a new rotational model that strengthens Nato’s integrated air and missile defence (IAMD) with regular training and rotation of systems across areas of responsibility.

Italy’s SAMP/T deployment marks the inception of the rotational model in Estonia. The concept was initially approved at the Vilnius Summit in 2024 and validated the following year in Washington DC, on the 75th anniversary of the alliance.

Components of the Italian system were strategically dispersed many metres apart in a linear fashion, minimising the destructive effect of potential adversarial attack.

A SAMP/T launcher can carry eight Aster 30 interceptor missiles. Credit: John Hill/GlobalData

The first component is an experimental radar built by the Italian defence manufacturer Leonardo.

Known as KRONOS GM HP (grand mobile high power), this new generation (NG), multifunctional, active electronically scanned array (AESA) radar was first produced in 2021. Leonardo completed factory acceptance tests for its fourth radar at the end of May this year.

KRONOS is not yet part of the operational SAMP/T system at the Estonian air base, but it will eventually replace the existing French radar component, built by Thales, that currently supports the air defence system.

The other operational radar component built by Thales for the SAMP/T, known as ARABEL, also conducts multifunctional, 360-degree tracking and identification of threats, but this system is an older passive electronic scanned array (PESA) radar.

This makes KRONOS more agile as the AESA capability means it can form multiple beams simultaneously at different frequencies whereas the ARABEL system is limited to a single, central, albeit powerful, transmitter.

This distinction impacts how each radar transmits, receives, and processes signals, resulting in a massive increase in the number of targets that KRONOS can track simultaneously. In effect, KRONOS has the capacity to detect up to 1,000 various targets compared to ARABEL’s capacity for up to 100.

Finally, the launcher sits on the back of a mobile platform. Each launcher has capacity for eight Aster 30 interceptor missiles.

While the system can detect threats at a range greater than 300km, the launcher intercepts air-breathing targets within a range of 150km. The solid propellant booster ensures the optimum shaping of the missile’s trajectory in the direction of the target and separates a few seconds after the initial vertical launch.

ARABEL radar system at Ämari Air Base at present. Credit: John Hill/GlobalData

Experimental radar – KRONOS – built Leonardo. Credit: John Hill/GlobalData

Two Italian F-35s flying in Estonia. Credit: Italian Air Force

Italian flag flying at Ämari Air Base, with military logistics vehicles. Credit: John Hill/GlobalData

One solution to this problem would be to include point‑defences on USVs.

William Freer, research fellow at the Council on Geostrategy

To modernise the platform, via an April request for information, the USAF is canvassing the inclusion of a new radar, electronic warfare equipment and enhanced

communications to create an “Advanced E-7”. Two such examples are sought within seven years, after which other E-7s could be retrofitted with the modifications.

As for the UK, three 737NG aircraft are currently undergoing modification in Birmingham, the first completing its maiden flight in September 2024.

Global Defence Technology asked Boeing what makes the E-7 stand out, and a spokesperson listing three points. First is its allied interoperability. “With the aircraft in service or on contract with Australia, South Korea, Türkiye, the UK and USA – and selected by Nato – its unmatched interoperability benefits a growing global user community for integration in future allied and coalition operations.”

The US is by far the largest spend on nuclear submarines. Credit: US Navy

Country | 2024 | 2025 | 2026 | 2027 | 2028 | 2029 | 2030 | 2031 | 2032 | 2033 | 2034 |

Australia | 3,582 | 3,586 | 3,590 | 3,594 | 3,613 | 3,622 | 6,183 | 6,207 | 6,216 | 6,239 | 6,380 |

China | 2,607 | 2,802 | 3,040 | 3,081 | 3,174 | 3,291 | 3,396 | 3,603 | 3,664 | 3,710 | 4,316 |

India | 2,320 | 2,533 | 3,675 | 2,457 | 2,526 | 2,639 | 2,741 | 2,873 | 2,958 | 3,350 | 3,560 |

Russia | 2,701 | 2,893 | 2,973 | 3,334 | 3,458 | 3,106 | 3,235 | 3,405 | 2,958 | 3,487 | 3,942 |

US | 16,957 | 18,037 | 18,522 | 18,607 | 18,137 | 18,898 | 18,898 | 19,643 | 19,876 | 22,592 | 23,730 |

Lisa Sheridan, an International Field Services and Training Systems programme manager at Boeing Defence Australia, said: “Ordinarily, when a C-17 is away from a main operating base, operators don’t have access to Boeing specialist maintenance crews, grounding the aircraft for days longer than required.

“ATOM can operate in areas of limited or poor network coverage and could significantly reduce aircraft downtime by quickly and easily connecting operators with Boeing experts anywhere in the world, who can safely guide them through complex maintenance tasks.”

Boeing also uses AR devices in-house to cut costs and improve plane construction times, with engineers at Boeing Research & Technology using HoloLens headsets to build aircraft more quickly.

The headsets allow workers to avoid adverse effects like motion sickness during plane construct, enabling a Boeing factory to produce a new aircraft every 16 hours.

Elsewhere, the US Marine Corps is using AR devices to modernise its aircraft maintenance duties, including to spot wear and tear from jets’ combat landings on aircraft carriers. The landings can cause fatigue in aircraft parts over its lifetime, particularly if the part is used beyond the designers’ original design life.

Caption. Credit:

Phillip Day. Credit: Scotgold Resources

Total annual production

Australia could be one of the main beneficiaries of this dramatic increase in demand, where private companies and local governments alike are eager to expand the country’s nascent rare earths production. In 2021, Australia produced the fourth-most rare earths in the world. It’s total annual production of 19,958 tonnes remains significantly less than the mammoth 152,407 tonnes produced by China, but a dramatic improvement over the 1,995 tonnes produced domestically in 2011.

The dominance of China in the rare earths space has also encouraged other countries, notably the US, to look further afield for rare earth deposits to diversify their supply of the increasingly vital minerals. With the US eager to ringfence rare earth production within its allies as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, including potentially allowing the Department of Defense to invest in Australian rare earths, there could be an unexpected windfall for Australian rare earths producers.