Feature

Autonomy and the Arctic

Situated in one of the most hostile environments on the planet, Arctic operations look towards autonomy. Helen Haxell-White reports.

Main image: The Arctic Ocean is an increasingly contested environment. Main video supplied by John Downer Productions/Creatas Video+ / Getty Images Plus via Getty Images

Feature

Taking stock: Europe’s rearmament quest

Europe greases the wheels of ammunition production through innovation and coordination – but is it enough? John Hill reports.

A hypersonic sled travelling at 6,400ft per second during a US test. Credit: US DoD

Whilst global political tensions heat up, uncrewed underwater vehicles (UUVs) and uncrewed surface vessels (USVs) are an emerging critical capability for operations in the depths of the Arctic, performing duties such as maritime domain awareness, surveillance, environmental surveys, and, potentially, warfare.

Playing their role in keeping human operators safe across all the warfighting domains (land, sea, and air), uncrewed systems are used to perform the so-called dull, dirty, and dangerous duties, as territorial claims and an increasingly contested battlespace intensify. For the Arctic, covered by ice for much of the year, subsurface platform autonomy will be paramount for regional states.

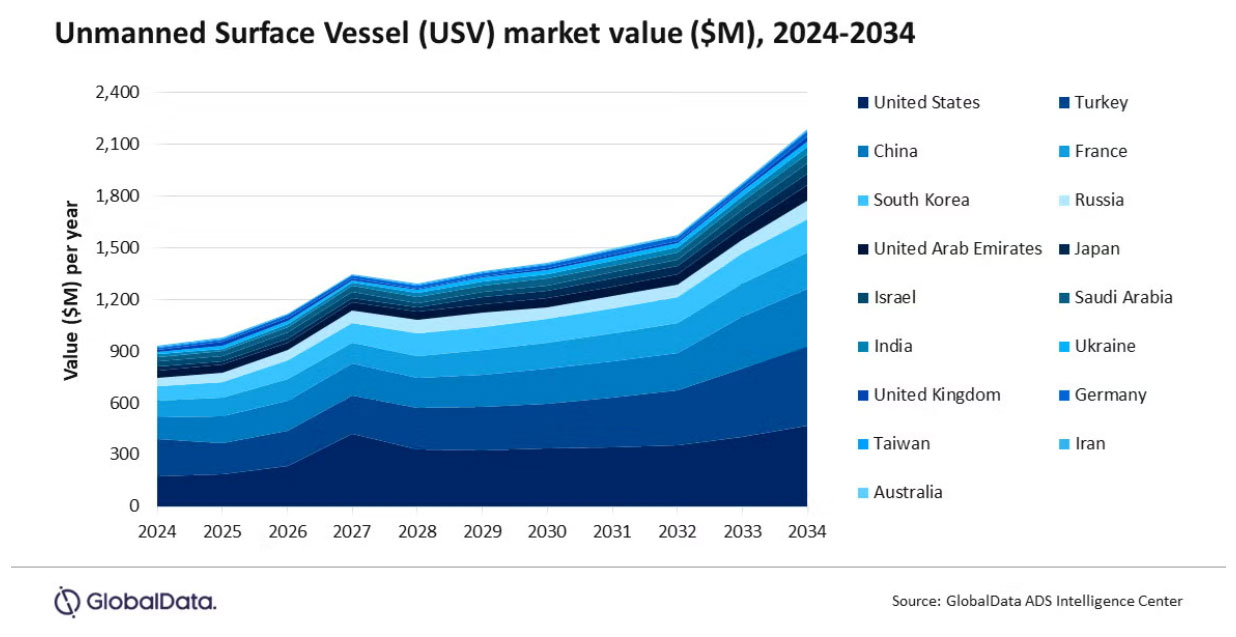

According to GlobalData forecasts the USV market will double over the next ten years. It is predicted that more than 40 countries will be operating the vehicles, and this will result in a 127% increase in the market from $1.1bn to $2.5bn.

The major market players, include Turkey, China, Russia, and the US, the latter two have a vested interest in the Arctic and are anticipated to grow their fleets and spend over the next decade. The significance of data management will also grow alongside the volume of the vehicles.

Deep Dive into the Arctic

Whilst the Arctic Ocean is the world’s smallest, it holds strategic importance as it spans the coastlines of eight countries, including Canada, Finland, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the US.

Dr Troy J Bouffard, director of Center for Arctic Security and Resilience (CASR), told Global Defence Technology about the roles played by these vehicles within the region: "UUVs and USVs give the Arctic persistent, risk-tolerant presence and capabilities for activities such as mapping ice and bathymetry, surveilling shipping lanes and subsea infrastructure, cueing search-and-rescue, and extending ASW and mine-countermeasure coverage at far lower cost and crew risk, directly improving regional safety and security.”

In order to protect the seabeds and secure the shorelines, nations are rapidly integrating UUVs and USVs into their naval fleets. The urgency of this capability integration was highlighted earlier in 2025 by Finland and Sweden who undertook a collaborative response to an underwater warfare incident in their shared waters.

The evolving scope of maritime incidents from sabotage of sea cables to provocative surveillance from hostile actors directly complicates maritime governance. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) sets out the guiding principles of what activities can be undertaken. However, the rise in vessels and multiple actors makes its enforcement weak and difficult to police.

A wedge test article undergoing trials in the US. Credit: USAF

Dr Romain Chuffart, president and managing director of The Arctic Institute, explained how legal framework redundancy means there is a lack of accountability due to operational ambiguity.

“Technological capacity itself is not sufficient to ensure either security or safety and these require deliberate governance, diplomatic interaction and clear norms. It must lead efforts to spark inclusive, multilateral discussions, ideally through the Arctic Council or International Maritime Organization, that can create codes of conduct for uncrewed platforms well in advance of crisis situations,” Chuffart said.

“Such conversations would encompass legal, operational and environmental considerations to safeguard the Arctic as a safe and stable space where technological advances work in the interests of cooperation rather than competition.”

Technological capacity itself is not sufficient to ensure either security or safety

Romain Chuffart, The Arctic Institute

Coordination of complex underwater activities is currently managed through the high-level Five Eyes international intelligence network and the Nato Alliance. However, the protocol of joint operations is underpinned through the vital development of Nato’s STANAG 4817.

This international standard centres on multi-domain command and control of uncrewed systems. Its implementation will enable vessels to operate and communicate with each other, through coordination over data exchanges and communications.

From an operational perspective, Cmdr Ryan Bell, Director of Naval Requirements 2 of the Royal Canadian Navy, highlighted the growing workload to Global Defence Technlogy for UUVs in the Canadian fleet, which serve across Canada’s three-ocean military area of operations.

For a mine clearing scenario, Bell said the best approach is through Nato allies collaborating. In this scenario, their vehicles enter into the water, use set parameters to scan the area, prioritise objects of interest for inspection, and then prepare for disposal.

“Only then, at that final moment when there is a kinetic action needed, would the system then say: ‘we've identified these mines. We have vehicles in the water ready to conduct kinetic disposal of these mines. Are you ready?’

“And there would be a seamless robotic cooperation between vehicles that were brought from a variety of different NATO nations that had ensured all of their systems, that they're procuring, were STANAG 4817-compliant,” Bell explained.

Autonomy: data management

As vessel deployment increases, so does the volume and variety of data they generate. Managing the data collected by high-end sensors is critical, as it can provide environmental monitoring and intelligence gathering.

Bell noted processing this amount of data, which can include extra information such as temperature or saline content, in addition to the main operational activity, is a challenge and an opportunity.

There's a lot of military and civilian work on big data processing happening right now

Cmdr Ryan Bell, Royal Canadian Navy

To ensure the data is used effectively, he suggested that maritime operation centres will likely leverage data management centres. A similar practice was adopted when satellite imagery was collected in large volume for military operations.

“There's a lot of military and civilian work on big data processing happening right now, and AI is really revolutionis[-ing] in that space. So, I think that we're moving in the right direction at the right time, but I think that will be a big challenge going forward,” Bell said.

The proliferation of UUVs and USVs by navies will bring an exponential amount of data but also a great amount of responsibility to ensure coordinated acts in operations as the waters get busy.

The adoption of uncrewed maritime vessels is going to double over the next ten years. Credit: Mstr Cpl William Gosse, Canadian Armed Forces

Dr Troy J Bouffard shared further: "As navies field these systems at scale, clear rules for under-ice operations, deconfliction and data-sharing as well as ecological sensitivities and safeguards against gray-zone use are essential so the deterrence and resilience they bring don’t come at the price of unintended negligence or miscalculation.”

To meet the decade's projected surge in UUVs, an immediate mandate for rigorous data management and operational accountability is required to secure future maritime order.

“That kind of decoupling is a lot more complicated than people would want to implement, and it's also a really expensive affair because it's not about just stopping the acquisition of new weapons. It's also about what you do with all of the training, the infrastructure, the planning for all of these contracts that are meant to last.”

Any breakup will also be painful for the US firms, which rely on partners to co-invest in research and systems development. The development and construction of F-35s is a project among allies, with components manufactured outside the US, including in Denmark and the United Kingdom.

“I think Lockheed Martin – as would the different subcontractors – would be very upset if there was any instability in the projected purchases of the F-35 from other countries,” said Bert Chapman, a professor at Purdue University and author of Global Defense Procurement and the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter.

Caption. Credit:

Phillip Day. Credit: Scotgold Resources

Total annual production

Australia could be one of the main beneficiaries of this dramatic increase in demand, where private companies and local governments alike are eager to expand the country’s nascent rare earths production. In 2021, Australia produced the fourth-most rare earths in the world. It’s total annual production of 19,958 tonnes remains significantly less than the mammoth 152,407 tonnes produced by China, but a dramatic improvement over the 1,995 tonnes produced domestically in 2011.

The dominance of China in the rare earths space has also encouraged other countries, notably the US, to look further afield for rare earth deposits to diversify their supply of the increasingly vital minerals. With the US eager to ringfence rare earth production within its allies as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, including potentially allowing the Department of Defense to invest in Australian rare earths, there could be an unexpected windfall for Australian rare earths producers.