INFORMATION WARFARE

OSINT in Ukraine: civilians in the kill chain and information space

OSINT shifted geopolitical sentiment toward Ukraine. Now members of the community are prosecuting the war through target acquisition. Andrew Salerno-Garthwaite investigates.

OSINT shifted geopolitical sentiment toward Ukraine. Now members of the community are prosecuting the war through target acquisition. Andrew Salerno-Garthwaite investigates.

Open-source intelligence (OSINT) has a long history of use in the intelligence community and the verification and crosschecking of evidence against data points is a standard tool for security services.

The war in Ukraine has been exceptional regarding civilian activity in verification of OSINT information, with large online open-source investigation communities and individual researchers sourcing and geolocating evidence before disseminating it to a public audience.

“Ukraine’s armed forces have outsourced parts of the kill chain to civilians,” writes Dr Matthew Ford, co-author of Radical War and associate professor of the Strategy Division of the Swedish Defence University, in the second of three 2022 working papers examining the war in Ukraine, The Smartphone as Weapon part 2: the targeting cycle in Ukraine.

In Ford’s paper he describes the widespread occurrence of civilians providing geolocated target information to the Ukrainian Army via smartphone technology. “The Ukrainian Armed Forces can then direct remote fire onto the targets that civilians have identified,” he writes, following verification by either intelligence services or the members of the OSINT community.

Challenges in processing the vast and diverse array of information have given rise to a need to standardise the induction of new data points. Ukrainians have been using a chatbot on social messaging platforms and an online webform to report the location of the occupying troops, providing consistent template for intelligence collection. “This made it possible for civilians to make direct contributions to the targeting cycle in actionable and speedy ways,” writes Ford.

In the Cold War, roughly 80% of information in a typical intelligence report actually came from open information, not secrets.

On 8 August, in Popasna, Ukraine, photos were shared on the Telegram social messaging network by a pro-Russian journalist that showed the local headquarters of a Russian Wagner paramilitary group. Clearly depicted on one photograph was the name plaque on the building displaying the address. It is unclear if Ukrainian intelligence officials combined this with existing information, but three days later the Ukrainian military reduced the building to rubble.

“Given the distorting effects of social media, however, it is unlikely that targeting is now being conducted exclusively on these platforms,” writes Ford. “Instead, a combination of sources is likely to provide the necessary information to allow Ukraine’s Armed Forces to target Russia’s military.

“It should be noted that integrating the targeting cycle into the civilian population implies Ukraine’s Armed Forces had themselves put considerable thought into how to fight like insurgents.”

OSINT has democratised intelligence

Independent defence analyst and author of the Covert Shores series, H I Sutton has attracted 169k followers to his Twitter channel CovertShores, and is respected for including significant original OSINT findings that have been born out with later confirmation and reported widely.

Sutton shares a sense of responsibility that is common in the OSINT community, to protect the channels and methods helping to unwind the truth of events behind the fog of war, but there are a number of points concerning OSINT and online open-source investigations that he was willing to describe for the benefit of decision makers in the services and the wider defence community.

“OSINT has democratised intelligence in the sense that any individual, and group or government has about the same access to the data. The differentiators will be motivation, organisation and effort,” wrote Sutton, in a message to Global Defence Technology.

The empowerment of technology and its international reach has drawn together unlikely characters under the cause of open-source investigation. Justin Peden is a 20-year-old Alabama University student that has followed events in Ukraine since the invasion of Crimea in 2014, and now runs one of the most followed Twitter accounts that documents the war in Ukraine, IntelCrab, with a following of 280,000. “I’m a broke college kid, but I have a lot of people donating to me essentially just so I can take my paycheque and splurge on satellite photos,” says Peden.

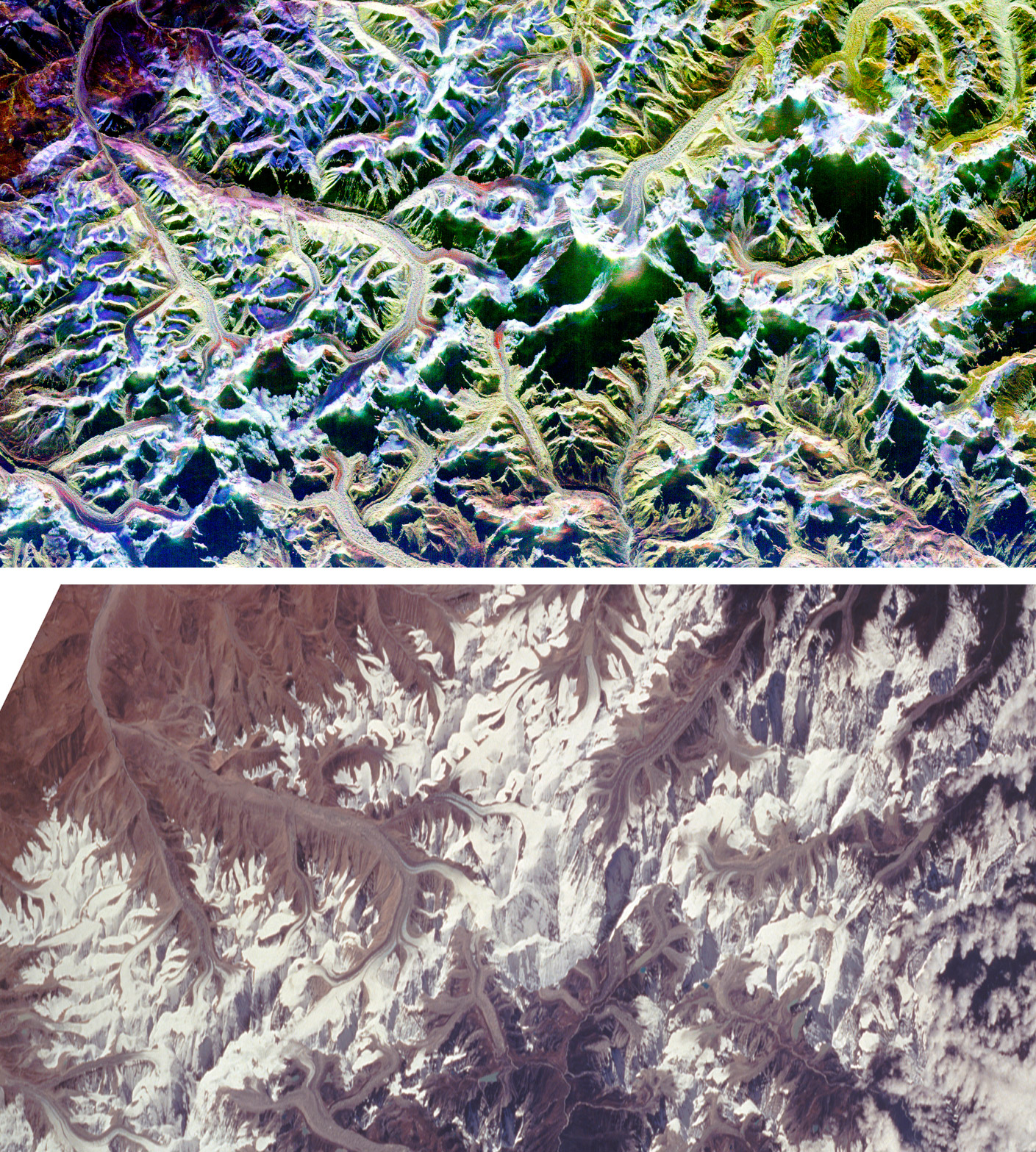

// Two comparison images of Mount Everest. The top image, which is a radar image, was acquired with Synthetic Aperture Radar onboard space shuttle Endeavour. The bottom image is an optical photograph taken by the Endeavour crew under clear conditions. Credit: CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images

The commercialisation of Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) satellites - a form of satellite photography that uses a projected signal instead of light - has allowed OSINT users to practise observation through night and day, and in all weather conditions. Though not as detailed as normal satellite photography, the applications have seen widespread use. “I do satellite intelligence a lot,” says Peden, “which I’m sure is a very popular one.

“A typical tweet process for me, when it comes from a social media standpoint, is; I hear a rumour; I sit on it. That’s just a lesson I’ve had to learn. I have a very thorough vetting process and a lot of that depends exclusively on primary sources, like photos and images.

“From an analytical standpoint, I have a lot of tools for looking at the metadata [of] videos, the metadata of photos, going beyond just a simple reverse Google image search to really find when a photo was taken. From there, it’s providing that context by geolocating, pinpointing it down under the map.”

Responding to questions about the use of OSINT in the prosecution of the war and in target acquisition, Peden has reservations about coming to conclusions, but he is clear about what he has observed. “This is very much tongue-in-cheek, but I do mean it,” says Peden, “there are isolated but growing incidents where that geolocation work, where those identified units, those identified vehicles, they are resulting in kinetic action… we have essentially geolocated Russian sites, Russian military bases, Russian infrastructure, and ‘coincidentally’… they’re destroyed 24 hours later.”

The relationship with traditional tools

There has been considerable excitement over the way OSINT has been adopted by a worldwide online community, and the utility and application of the findings they have developed. Sutton addresses the enthusiasm for this evidence base over other sources. “OSINT should not be seen as a challenge to traditional intelligence gathering, but a complement,” writes Sutton, adding a cautionary note against vanguardist influences: “Do not let old-school intelligence interests limit your OSINT use.

“At the same time, do not neglect continued investment in traditional intelligence, OSINT is not a replacement. Getting this wrong would only increase infighting and, ultimately, inefficiency.

“Another challenge is that your commanders in the field may be receiving their own OSINT. Especially if traditional intelligence is not being shared. This has pros and cons but is bound to cause organisational tensions.”

// The availability of information has enabled a far greater spread of people to analyse military operations, including those in the civil space. Credit: Shutterstock

OSINT has produced significant findings disclosing egregious Russian actions and dispelling Russian explanations. In early March, OSINT verified that the Russian Air Force (VKS) used unguided “dumb bombs” against civilian targets. After an airstrike in Chernihiv killed 47 civilians, OSINT investigators found an unguided FAB-500 M62 bomb had been used, following a review of video footage from the strike location that showed an unexploded sample of the munition being removed. Further confirmation was ascertained three days later when the VKS released a video showing a Su-34 armed with eight FAB-500 bombs.

A notorious example of the use of open-source satellite intelligence in the information space comes from Bucha, where a massacre of civilians left the executed bodies in a street occupied by Russian forces, with the victims later discovered by advancing Ukrainians.

In an exercise to control the narrative of events, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov claimed that Ukrainians had used cadavers to stage the scene after Russian forces had retreated. Visual journalists at the New York Times debunked this account using satellite imagery from MAXAR to disprove these assertions. The images showed that the bodies had been present in the streets nearly two weeks before Russian forces retreated and were verified and cross-referenced it with later video footage from the site.

Metadata analysis has also found a place as a tool of use in the information space. On the 18 February, five days before the Russian invasion, Luhansk and Donetsk authorities published a video that they claimed was contemporary footage of an emergency evacuation of separatist-held areas following a Ukrainian escalation, in an attempt to create a narrative of Ukraine aggression against civilians in these regions. However, OSINT investigation of the video metadata filmed on 16 February, two days earlier than stated, calling into question its provenance and validity.

The value of secrecy

“Traditional intelligence methods using state apparatus will still have advantages,” writes Sutton, reflecting on the implementation of OSINT findings in a modern intelligence context. “But the intelligence gap between top-tier militaries and their potential adversaries may be much less than in the past.”

Speaking on an episode of the Babbage podcast, Dr Amy Zegart, author of “Spies, Lies and Algorithms” and a political scientist studying US intelligence at Stanford University, lamented the widespread adoption of OSINT by the civilian community, on 10 August 2021: “Open-source intelligence is dramatically democratising the ability of just about anybody to collect and analyse important information, and that's bad for the United States. It means that the United States is losing its relative intelligence edge.

“In the Cold War, roughly 80% of information in a typical intelligence report actually came from open information, not secrets.

“The value that intelligence agencies have historically played is marrying that open-source intelligence with the documents … or intercepted telephone communication,” continued Zegart. “But what's happened today is that open-source intelligence is now foundational. This information is fully transparent. Secrecy in some ways gets a bad rap. Secrecy provides room to manoeuvre, room to de-escalate, room for both sides to save face in a crisis.”

These concerns, voiced by Zegart last year, should be balanced against the benefits transparency has since brought to the geopolitical calculation for allied western powers seeking deeper support for the defence of Ukraine.

“OSINT can also be used in information warfare, for example, to show the Russian build up before the invasion,” writes Sutton, describing the effect of transparency, brought about by OSINT, on the discourse coming up to the Russian invasion.

In the weeks before the date of the invasion, US intelligence was able to publicly confirm a Russian build-up that had been described through open-source accounts and used disclosure of open-source evidence to warn against possible false-flag narratives that Russia may have alleged. The effect was to expose the public to the prospect of war in Ukraine and galvanised an international response.

I think it would be great if somebody noted that the Internet overall, and the community in particular, showed the undeniable, overnight ability to kind of take a side. To choose - almost with ‘scout’s honour’ - to say: ‘I won’t share Ukrainian [military information]’.

After the invasion, the information space was saturated with images coming from Ukraine that ran contrary to the expectations of defence analysts that had predicted a swift and decisive victory for Russia. The professionalisation of Ukraine’s military forces in the years since the invasion of Crimea and Russia’s difficulty in command-and-control structures began to be clear, with quickly reported images of Russian land platforms that were either destroyed or abandoned becoming ubiquitous on social media.

The effect of these well-reported early Ukrainian successes, elevating the estimation of the cause’s potential - from ‘hopeless’ to ‘surmountable’ - motivated the public to support deeper veins of military aide.

While OSINT has brought some distinct successes as technology becomes more abundant, Sutton has reservations about its future in the context of potential state intervention. “OSINT is fragile, it is largely dependent on the indiscretion of others. However, efforts to close it off to an enemy are unlikely to be fully successful.

“Liberal democracies, with extensive personal freedoms and norms of internet use, will have more challenges managing OSINT exposure than authoritarian states. Fake news and disinformation will leverage OSINT, both genuine and misleading information.”

Peden, speaking during a work-break in a long shift at the local radio station where he has a summer job on the news desk, describes the OSINT community in warm tones, with respect for its work: “I think it would be great if somebody noted that the Internet overall, and the community in particular, showed the undeniable, overnight ability to kind of take a side. To choose - almost with ‘scout’s honour’ - to say: ‘I won’t share Ukrainian [military information]’.

“That happened so drastically, overnight, with no sort of obligation to do so. And it’s definitely a really cool thing, the more I think about it, because I take it for granted when I go on Twitter I only see: ‘Russia was here. Russia was there. They got blown up. They lost this. They lost that.’ So, it’s a cool thing.”

// Main image: Use of open-source intelligence by civilian analysts of the Ukraine war is widespread and could have been used for geo-locating Russian forces. Credit: Shutterstock