Feature

India vs Pakistan: a military comparison

Air and missile strikes between the two countries broke out in May, before a tentative cessation of hostilities was agreed. Richard Thomas reports.

Hostilities between India and Pakistan once again broke out in May. Credit: Tomas Ragina / Shutterstock

No stranger to armed conflicts, India and Pakistan have developed capable military forces able to conduct operations across the warfighting spectrum. Both countries, to a greater or lesser degree, rely on defence imports, with Russia and China leading respective suppliers.

Tensions between India and Pakistan ratcheted up in May this year following the April terrorist attack in Indian-administered Jammu and Kashmir, which Delhi blamed on Islamabad, which in turn denied the allegations.

Such tensions snapped on the evening of 6 May, when India launched a series of missile strikes into Pakistan-controlled Kashmir and Pakistan itself. Resultant exchanges of fire have seen both sides claim success, with Pakistan stating on 7 May it had shot down five Indian jets, according to a Reuters video report.

A subsequent cessation of hostilities, supposedly as a result of negotiations with the United States, and a relative calm once again returned to the borders. However, with the two countries, both nuclear powers with a previous history of armed conflict, at continuous risk of a return to hostilities, Global Defence Technology compares key capabilities in their respective militaries.

India vs Pakistan: defence spending

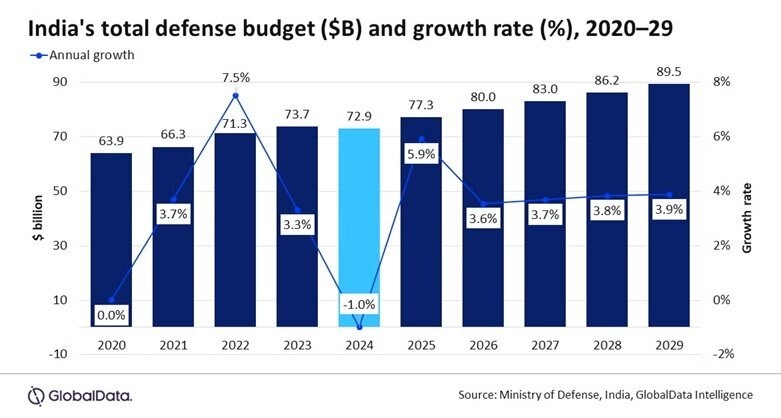

According to analysis conducted by GlobalData in late-2024, India was forecast to invest heavily in order to sustain readiness for a potential two-front conflict with regional adversaries China and Pakistan.

Total defence spending, inclusive of pensions, was projected to reach $415.9bn from 2025 to 2029, marking a compound annual growth rate (CAGR).

In the 2024 report, ‘India Defense Market Size, Trends, Budget Allocation, Regulations, Acquisitions, Competitive Landscape and Forecast to 2029,’ GlobalData detailed India’s need to modernise its defence inventory while reducing dependence on imports.

Key acquisition programmes include nuclear-powered attack submarines, Nilgiri-class guided missile frigates, Rafale and Tejas Mark 1A multirole fighter aircraft, Prachand Helicopters, and the Zorawar main battle tank (MBT).

This Philippine Army soldier has an L3Harris handheld radio fitted in a harness hung around his neck. Credit: Gordon Arthur

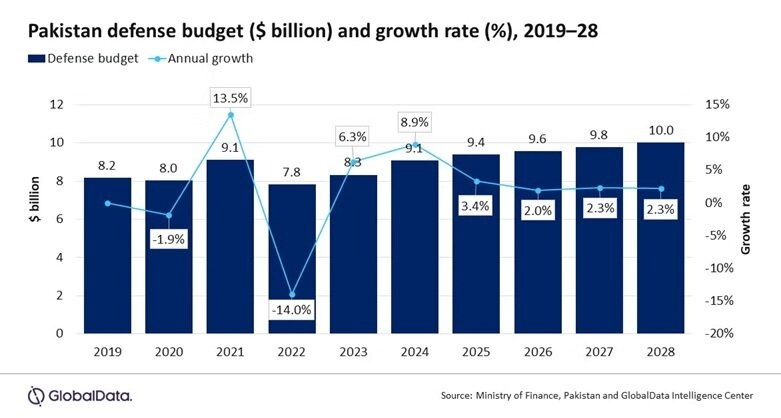

By contrast, Pakistan’s annual defence budget was forecast to reach $10bn by 2028, growing at a CAGR of 2.5%, according to a late-2023 report by GlobalData.

Influencing factors included Pakistan’s efforts to secure its borders and maintain stability within the country, with challenges such as Pakistan’s volatile relationship with its neighbours and regional separatist movements, playing a major role in influencing the country’s defence policy making.

This Philippine Army soldier has an L3Harris handheld radio fitted in a harness hung around his neck. Credit: Gordon Arthur

These factors are expected to continue to drive Pakistan’s defence budget to an estimated $10bn by 2028, with a CAGR of 2.5%, according to GlobalData.

A sharp 14% decline in defence spending in 2022 was a low point, dropping to $7.8bn, although subsequent increases have served to provide new capabilities for Pakistan, through ongoing and planned purchase of platforms like the FC-31, J-10C, PAC PF-X, and JF-17 Block-3 multi-role aircraft.

India vs Pakistan: air domain

Fleet inventories gathered by GlobalData’s defence intelligence centre details the capabilities that both countries have in the air domain, each with sizeable fixed-wing combat aviation forces.

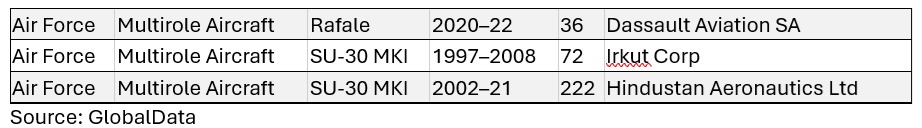

India’s main air combat element is maintained through its ~220 Su-30 Mk1 fighters produced by Hindustan Aeronautics and delivered between 2002-21, from the original Russian design. A smaller 72-strong fleet of Su-30 Mk1 aircraft was provided by Irkut Corp between 1997-2008.

The newest air combat element of the Indian Air Force is the 36 Rafale multirole fighters from French OEM Dassault, delivered between 2020-2022. The Rafale is judged to be a 4.5 generation platform, with advanced avionics and electronic systems, and roughly analogous to the Eurofighter Typhoon.

Rohde & Schwarz is supplying thousands of Soveron-based radios to the German Armed Forces. Credit: Rohde & Schwarz

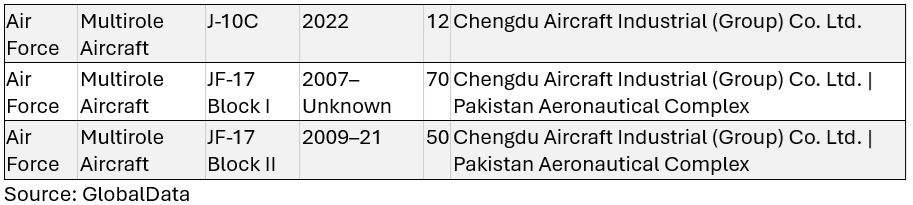

Pakistan operates some US and French origin fighters, such as early model F-16A/B Fighting Falcons and old Mirage 2000 jets. However, in recent years it has leaned heavily into China’s export market, introducing a range of fighters produced by Chengdu Aircraft Industrial Group, with the Pakistan Aeronautical Complex involved also involved in more recent batches.

Rohde & Schwarz is supplying thousands of Soveron-based radios to the German Armed Forces. Credit: Rohde & Schwarz

All told, Pakistan has around 120 aircraft of the JF-17 Block I and Block II variants, delivered between 2007-2021, as well as 12 newer J-10C fighters, in 2022.

India vs Pakistan: land domain

India and Pakistan maintain rounded armies, with an emphasis on armoured vehicles and artillery, which sometimes exchange fire across their respective lines of control.

The Indian Army has more than 2,000 BMP-II armoured personnel carriers/infantry fighting vehicles from the K and M models, produced by India’s own defence industrial base from the Russian design from the 1980s through to the present day.

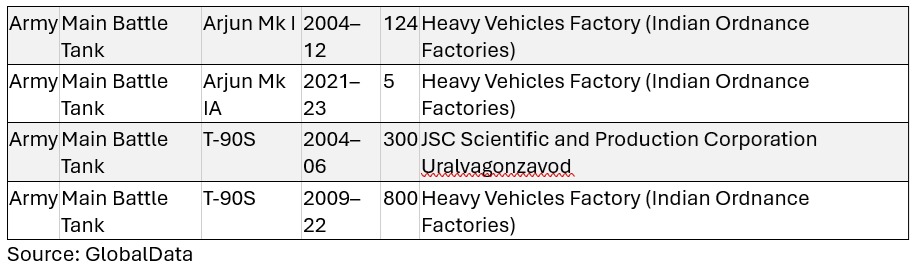

In terms of MBT fleets, India maintain a mix of Russian origin and indigenous designs, with the more capable T-90S and early model Arjun Mk1A tanks at the forefront.

L3Harris Technologies is supplying Falcon IV AN/PRC-158 manpack radios under the US Handheld, Manpack & Small Form Fit project. Credit: L3Harris

Artillery is provided mainly via the 100-strong K9A1 self-propelled howitzer force as the most modern capability available, delivered from 2018-2021.

Indian ground-based air defence systems include ~80 of the 2K22M ‘Tunguska’ system for use at the tactical level, and the highly advanced Russian S-400 and Israeli-origin Barak-8 systems for long-range intercept.

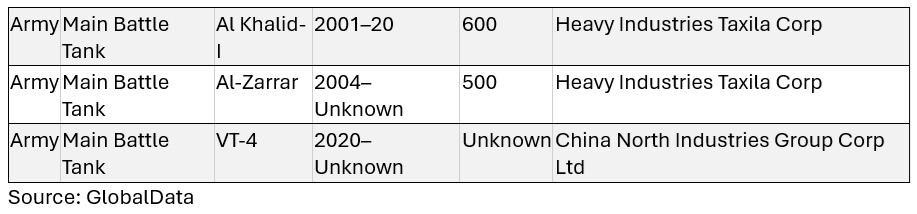

Pakistan’s relationship with China is also showcased in its heavy armour fleets, with all of its MBTs either produced by or adapted indigenous variants of Chinese designs. This includes around 600 of the Al Khalid-1 MBTs, co-developed by Norinco and Heavy Industries Taxila Corp.

Other Norinco platform such as the VT-4 are also operated, likely in fleet several hundred strong.

L3Harris Technologies is supplying Falcon IV AN/PRC-158 manpack radios under the US Handheld, Manpack & Small Form Fit project. Credit: L3Harris

Pakistan’s artillery capability is delivered via US-origin M109A5 155mm SPHs, which have a firing range of around 25-30km. Both countries maintain inventories of towed artillery, which are positioned along border flashpoints.

In terms of ground-based air defence, Pakistan operates an integrated layered system, comprising the long-range HQ-9/P that has a claimed intercept range of up to 125km, and the medium-range LY-80 and LY-80EV system for threats up to 70km distant.

India vs Pakistan: naval domain

Given the likely focus on air and long-range fires capability, the current state of conflict between India and Pakistan is not likely to warrant extensive use of naval capabilities. However, details of major surface combatants, and perhaps most crucially, submarine fleets, are worth inclusion.

India is among the top five global spenders in nuclear-powered submarine programmes, according to analysis conducted by Global Defence Technology affilated naval news site Naval Technology, ranking fifth with a forecast spend of $34.6bn between 2024-2034.

Of this, 30.5% will be directed towards the procurement of Project 75-Alpha SSNs during the same period, with India is expected to acquire a total of six SSNs under this programme at an estimated value of $17bn. In addition, the Indian Navy operates more than a dozen diesel-electric submarines, ideal for littoral operations and covert warfare.

The Indian Navy has commissioned the aircraft carrier INS Vikrant into its fleet. Credit: Indian Ministry of Defence

India also maintains two aircraft carriers, the INS Vikrant, the first domestically built carrier to enter service, and the INS Vikramaditya, a former Russian Kiev-class vessel. Assorted surface escorts include the nine Project 15/A/B class destroyers and four Kamorta-class corvettes.

The Pakistan Navy is a significantly smaller proposition, operating no aircraft carriers or amphibious assault ships. While its surface combatant force is relatively small, it does contain four 4,200-tonne Type 054 A/P frigates, built by China’s Hudong-Zhonghua Shipbuilding, and four F-22P frigates, produced jointly by Chinese and Pakistani shipyards.

Subsurface warfare capability is limited, thought to be provided by up to five ageing Agosta-class diesel electric submarines.

India and Pakistan: nuclear weapons

Perhaps most pertinent is that both countries are so called ‘unrecognised’ nuclear weapon states, and not signatories to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT).

According to the Arms Control Association, India and Pakistan have around 170 nuclear warheads apiece, and pursue a range of delivery methods, including ballistic missiles, such as the Indian Agni-P.

A reliable first-strike capability that results in near-elimination of a devastating retaliatory capability is not feasible

Dr Tom Stefanick, non-resident senior fellow, Brookings Institution

We are always looking for opportunities that innovative technologies potentially offer to improve our training delivery

Commodore Steve Jose, UK MFTS head

Caption. Credit:

Phillip Day. Credit: Scotgold Resources

Total annual production

Australia could be one of the main beneficiaries of this dramatic increase in demand, where private companies and local governments alike are eager to expand the country’s nascent rare earths production. In 2021, Australia produced the fourth-most rare earths in the world. It’s total annual production of 19,958 tonnes remains significantly less than the mammoth 152,407 tonnes produced by China, but a dramatic improvement over the 1,995 tonnes produced domestically in 2011.

The dominance of China in the rare earths space has also encouraged other countries, notably the US, to look further afield for rare earth deposits to diversify their supply of the increasingly vital minerals. With the US eager to ringfence rare earth production within its allies as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, including potentially allowing the Department of Defense to invest in Australian rare earths, there could be an unexpected windfall for Australian rare earths producers.