Feature

Naval blueprints: origins and fate of warship design

Competitive warship acquisition pitches designs against each other to find a winner. But what happens to those not selected? Richard Thomas reports.

Naval designs not chosen for build can still serve a purpose for industry. Credit: BMT

At the outset of a naval procurement programme, the customer, usually a ministry or department of defence and its maritime service, will set out a series of requirements to industry that the platform must adhere to, in terms of dimensions, capability, and often cost.

Industry then sets about designing a warship to meet these demands, trying to find the perfect balance of requirements to hopefully win the day come contract award time.

However, less is known of the designs that are not selected, the product of countless hours of development, with the perception that they are immediately cast out of the public eye to rest on a digital shelf somewhere, to all intents and purposes, forgotten.

The real story is more complex, with ‘unsuccessful’ designs sometimes serving to inform future platforms and programmes, or else going on to find success elsewhere in the competitive global naval warship sector.

In exploring the fate of unsuccessful designs that have been entered into naval procurement competitions, Global Defence Technology goes in-depth into the UK’s Type 31 programme, a platform that was initially conceived as a light frigate but since gone onto offer a full surface warfighting spectrum.

Basics of the Type 31 programme

A little over five years ago, in 2019, the contract award for the build of five new Type 31 frigates for the UK Royal Navy was announced, the culmination of years of competition that saw a range of ship designs sourced from across Europe pitted against one another, with the win going to Babcock and its Iver Huitfeldt-derived platform.

However, while Babcock began the process of turning a digital image into a steel warship, the other designs and their respective industry owners were left to consider their options, and what next steps might be taken to ensure their continued relevance or consignment to naval history.

In the second running of the Type 31 programme (after the 2018 restart), the design options consisted of the BAE Systems Leander-class concept, Stellar Systems’ Spartan platform, TKMS’ Meko-200 design, as well as Babcock’s successful Arrowhead 140 offering, based heavily on the Danish Iver Huitfeldt-class frigates.

In addition, earlier designs mentioned in public for the abortive first run of the programme included an enlarged BAE Systems Batch 2 River-class offshore patrol vessel, Stellar Systems’ Spartan concept, as well as BMT’s Venator-110 design.

This analysis has benefitted from background insight from industry to aid in data collection, and, where possible, on-the-record comments from the experts involved in naval warship design.

Stellar Systems: Spartan

Issued from out of left field, Stellar Systems’ Project Spartan design was pitched in 2017 as a “configurable, modular, survivable, affordable and exportable ship”, with a focus on “packing as much UK industrial capability and UK equipment into an attractive package”, the company stated at the time.

Showcasing its design, Stellar Systems announced in its public brochure that it had taken a “Nodal Modular Physical Architecture” approach to the design, enabling for configurable weapons and systems options, citing examples of switching in a 30mm small calibre gun or SeaRAM/Phalanx CIWS in place of the forward Mk 41 vertical launch system (VLS).

Although length and displacement details were not included in the publicly released data sheets, the design showed a 76mm main gun fitted forward with a Mk 41 VLS located immediately behind, in addition to twin 20-30mm secondary gun fitted behind the bridge. A Phalanx CIWS sits on top of the ship’s hangar, while two quad-stacked anti-ship missile canisters are fitted amidships.

The Spartan concept, although not selected for Type 31, has gone onto influence future designs. Credit: Stellar Systems

A large twin-door hangar was designed to accommodate medium-sized helicopters, and an uncrewed rotary platform, with a below-landing deck launch bay containing the ship’s rigid-hulled inflatable boat (RHIB), launched via a stern ramp.

The design was not part of the 2018 re-run of the Type 31 programme. However, in May 2024 Stellar Systems unveiled its Fearless littoral strike ship concept, a 170m-long vessel design for a prospective Multi-Role Support Ship requirement that will provide amphibious and littoral effect capability to a Royal Marine Commando-centric force.

In a company update posted on its site in June 2024, Stellar Systems made its case for the Fearless and other naval platform designs unveiled, adding that “while [its] designs garnered most of the attention, [the company’s] core strength lies in being a naval architecture and marine engineering consultancy”.

Common themes that look to have ported across from the Spartan to the Fearless designs include the inclusion of large, modular hangars and open spaces, a design concept that is gaining increasingly popular among the next generation of warships.

BMT: Venator-110

Early in the first run of the Type 31 programme, naval design specialists BMT proposed the Venator-110 concept, envisaging a light frigate of around 4,000 tonnes displacement able to reach speeds of 25kts. The design envisaged a warship equipped with main gun system from 57mm up to 127mm, featuring modular missile options to include canister-launch anti-ship missiles and variable layouts for anti-air warfare munitions.

The Venator-110 was designed to be “lean-manned”, likely with a crew of under 100 core sailors, augmented with an embarked helicopter unit.

While the design did not make it through to the final options being considered, elements of the BMT design team went on to contribute to the Babcock-led Team 31, which ultimately won the Type 31 competition with its Iver Huitfeldt-derived AH-140 offering.

Produced by BMT, the Venator-110 design is still used to test naval concepts. Credit: BMT

In addition, the design is still in use as a concept for use by BMT to investigate future technologies in the naval sector, and as such maintains a relevance despite having not been selected for Type 31.

Andy Kimber, BMT’s chief naval architect, told Global Defence Technology that although Venator was not selected as the offer from (future Babcock-led) Team 31, much of the learning in developing the design at a systems level and consideration of suitable mission system solution was taken forward, as BMT designers also continued to work in the Team 31 structure through the competitive and subsequent delivery phases.

“Whilst we may not be promoting Venator as a design, we continue to promote our people in support of the system integrators/complex warship build yards. Venator as a concept remains a great R&D tool to explore future fuels, automation technologies, for the next generation warships and also provides a way to hone skills in our people,” Kimber said.

Specific to this was Venator’s use as a “vehicle for conducting research and testing idea” where it has “supported BMT’s initiatives in understanding crew reduction and increased automation, alternative mission and combat system configurations as well as much research into understanding the tailoring of survivability characteristics against threat environments,” Kimber explained.

BAE Systems/Cammell Laird: Leander

Birkenhead shipbuilder Cammell Laird and UK defence prime BAE Systems put forward the Leander frigate concept for the Type 31 programme and wider export markets, designing a platform that was available in four sizes: 99m, 102m, 117m, and 120m.

The design, at its base, was a stretched version of the 99m Khareef-class corvette, of which three were built for the Royal Navy of Oman in the mid-to-late-2000s by BAE Systems. Likely displacing in the region of 3,500 tonnes, the Leander frigate was to feature a typical combat layout of medium main gun, usually depicting a 76mm system, as well as 30mm secondary armament and a Sea Ceptor VLS (as used on the Type 23 frigates) for anti-air warfare, mounted forward of the bridge.

Additionally, promotional imagery also depicted canister-launched anti-ship missiles, mounted amidships, for surface warfare requirements. Space was also available for the installation of a Mk 41 VLS, while sensors included the Artisan Type 997 radar, a common system fitted to in-service Royal Navy vessels.

The Leander light frigate bore a heavy resemblance to Oman’s Khareef corvettes. Credit: Cammell Laird / BAE Systems

However, the main shift from the Khareef to the Leander was in the incorporation of three mission bays, each of which would be able to accommodate an ISO container to modular mission packs depending on the expected role.

With BAE Systems’ shipyards at Govan and Scotstoun busy with the build of the Type 26 anti-submarine warfare frigates through the 2020s and into the following decade, Cammell Laird’s shipyard would be tasked with manufacturing the five warships, should it have been selected. The site is currently used by the Royal Navy and Royal Fleet Auxiliary as a maintenance and repair facility.

Despite the pitch, the design was not selected for the Type 31 programme, with no further work being performed on it since 2019.

However, BAE Systems though looks to be maintaining its interest in naval warship design, potentially taking on lessons learned during the Type 31 process, unveiling in 2022 at the Euronaval exhibition near Paris the concept design of a new platform – the Adaptable Strike Frigate (ASF). A more modern platform compared to the Leander, BAE Systems has promoted the design in the UK and around the world as a light frigate solution for international navies.

Atlas Elektronik UK/TKMS: MEKO A-200

An outlier for the UK frigate programme saw the UK presence of Germany-based Atlas Elektronik team with German naval prime ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems (TKMS) to offer the Mehrzweck-Kombination (MEKO) A-200 design, with the build planned to take place at Harland & Wolff in Northern Ireland and Ferguson Marine in Scotland.

Since the award of the Type 31 programme in 2019 both Harland & Wolff and Ferguson Marine have been hit by financial difficulties, with the former now in administration and the latter requiring bail outs by the Scottish government.

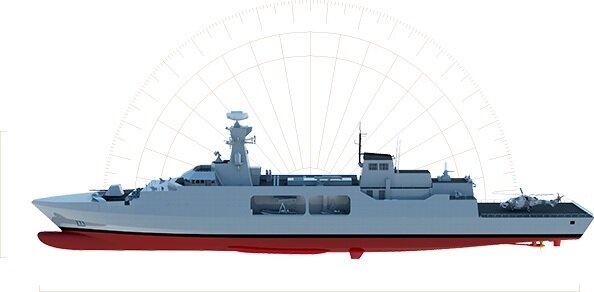

The MEKO A-200 was an outlier in the Type 31 competition, but has achieved global export success. Credit: TKMS

Variants of the A-200 have found their way into service with the navies of South Africa, Algeria, New Zealand, and Turkey, among others, featuring a range light to medium-heavy weapons fittings, including the RBS-15 anti-ship missile and OTO Melara 127mm main gun systems.

Displacing around 3,500 tonnes, depending on outfitting, the A-200 was pitched as a light frigate-sized platform, but required around 200 crew for effective operations. This is significantly higher than other alternatives and more than the Type 23 frigate already in service with the Royal, which the Type 31 was intended to in-part replace.

The A-200 was considered an outsider, and although being selected into the final three-design shortlist was ultimately unsuccessful. TKMS still markets the A-200 platform to international navies.

Babcock/Team 31: Arrowhead 140

Ultimately, after the 2018 restart and subsequent shortlist, Babcock’s Team 31 effort and the AH-140 offering came out on top with its design getting the nod from the UK MoD in 2019.

Perhaps most notable has been the growth in platform size from the 2017 light frigate requirement, with the AH-140 Type 31s now likely to displace around 5,700 tonnes, and potentially more as new capabilities are added.

What has been prioritised is space, with a modular mission bay able to accommodate a range of potential mission payloads, a design principal that was present throughout the Type 31 competition. Propulsion has been kept simple, in a combined diesel and diesel (CODAD) configuration, following the Royal Navy’s troubles with more complex systems, as seen with the Type 45 air defence destroyers.

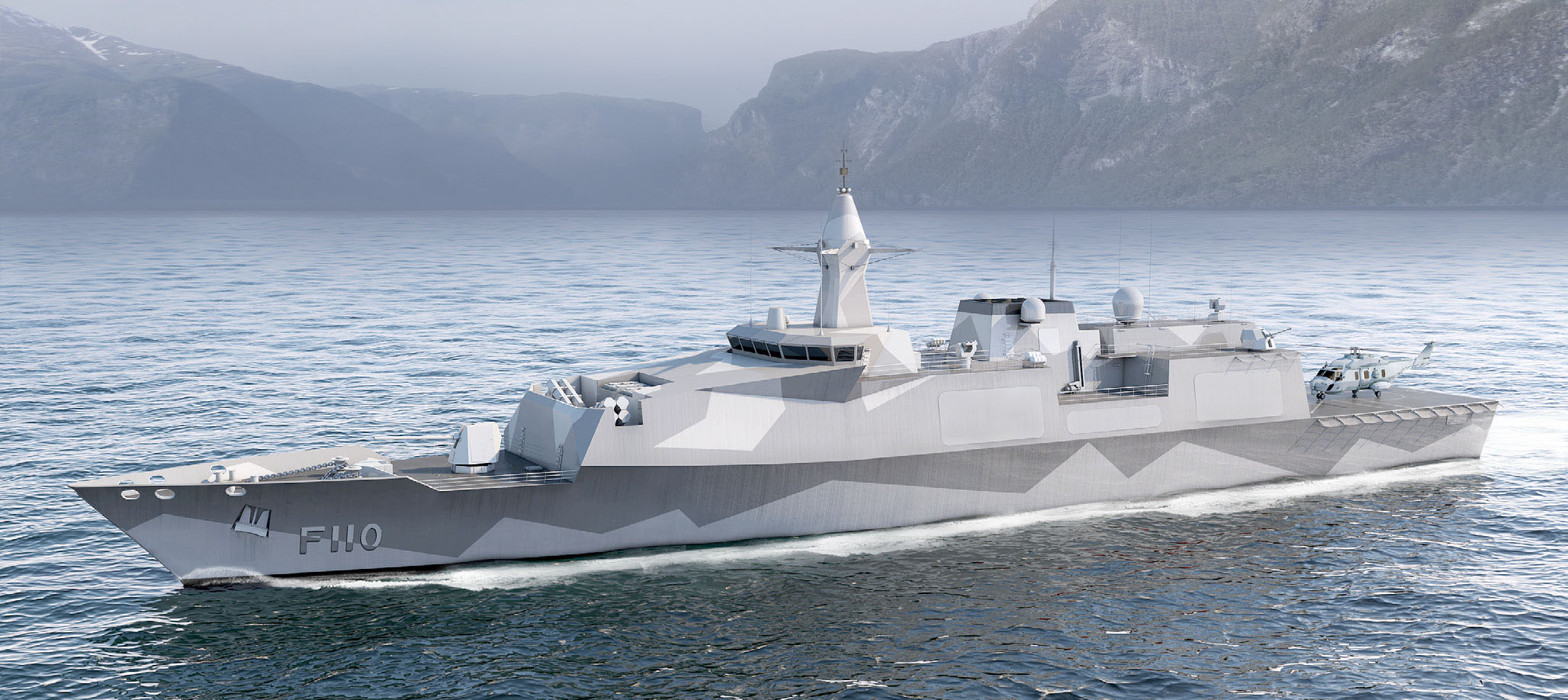

The AH-140, based on OMT’s Danish Iver Huitfeldt frigates, was ultimately selected for Type 31. Credit: Babcock

The Type 31s weapons fit has also evolved to now include the Mark 41 VLS, although it is possible that early ships in class, being built to the earlier configuration, might have to have the system fitted during a capability insertion programme during a mid-life upgrade.

Babcock is building the vessels at its Rosyth facility, investing heavily into naval infrastructure at the site including the delivery of a new shipbuilding hall, with the yard likely well-placed to secure future Royal Navy deals for further Type 31 frigate, or perhaps the mooted (but still in concept) Type 32 platform.

The AH-140 has also seen export success, winning prorammes in Poland (for three ships) and Indonesia (two ships), indicating that the UK was not alone in seeing a preference for the design, which has its origins with Odense Maritime Technology’s (OMT) Danish Iver Huitfeldt-class frigate built in the late-2000s.

Naval design more evolution, than revolution

In summary, a naval design that falls short of the finish line need not represent the death knell for a concept as the work put into the programme feeds into a company’s future efforts, or going on to success in other competitions. Throughout the Type 31 process, common features emerged from among all the competitors, particularly in modular mission bays.

Warship design can still serve a purpose as concepts and trends evolve or the years. Credit: BMT

As Kimber outlined, such concepts also served as an opportunity to further develop the skills of naval designers and engineers, training the next generation of professionals learning the ropes ahead of the next Type 31 programme offering.

This could come sooner than thought likely, with a Type 32 multi-mission warship at early concept stages with the UK Ministry of Defence, while the future Type 83, the replacement for the in-service Type 45, offers new opportunity for industry to put into practice carefully honed design skillsets.

We've been out there communicating with our key security cooperation partners, especially the UK

Frank Lazzara, director of Advanced Vertical Lift Systems Sales and Strategy at Bell Textron

Caption. Credit:

Phillip Day. Credit: Scotgold Resources

Total annual production

Australia could be one of the main beneficiaries of this dramatic increase in demand, where private companies and local governments alike are eager to expand the country’s nascent rare earths production. In 2021, Australia produced the fourth-most rare earths in the world. It’s total annual production of 19,958 tonnes remains significantly less than the mammoth 152,407 tonnes produced by China, but a dramatic improvement over the 1,995 tonnes produced domestically in 2011.

The dominance of China in the rare earths space has also encouraged other countries, notably the US, to look further afield for rare earth deposits to diversify their supply of the increasingly vital minerals. With the US eager to ringfence rare earth production within its allies as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, including potentially allowing the Department of Defense to invest in Australian rare earths, there could be an unexpected windfall for Australian rare earths producers.