Comment

How defence stocks’ staying power translates into investment strategy

Christopher Granville, managing director at GlobalData TS Lombard, explains what investors should know about the surge in demand for military equipment caused by the Russia-Ukraine war.

A Ukrainian tank column on exercise prior to Russia’s invasion of the country. Credit: Shutterstock/ khorkins

Long-run macro themes can be tricky to translate into equity portfolio strategy, but war could prove an exception to this rule. The resulting prospect of sustained expansion of government demand for military equipment is an argument at least for a passive strategy – on the rising-tide-lifts-all-boats rationale – of overweight exposure to defence sector stocks.

Their relative outperformance since Russian invaded Ukraine eighteen months ago will not just be supported by the dire prospect of the war dragging on but should also extend into the ensuing cold peace. This investment thesis passes the test of at least three possible objections.

Royal Navy Type 23 frigate | Planned OSD |

| HMS Argyll | 2023 (entered LIFEX in 2022) |

| HMS Lancaster | 2024 |

| HMS Iron Duke | 2025 (entered LIFEX in 2022) |

| HMS Monmouth | 2026 (actual 2021) |

| HMS Montrose | 2027 (actual 2023) |

| HMS Westminster | 2028 |

| HMS Northumberland | 2029 |

| HMS Richmond | 2030 |

| HMS Somerset | 2031 |

| HMS Sutherland | 2032 |

| HMS Kent | 2033 |

| HMS Portland | 2034 |

| HMS St Albans | 2035 |

A table showing the planned OSD for the Type 23 frigate. Brackets indicate potential/confirmed changes. Credit: GlobalData

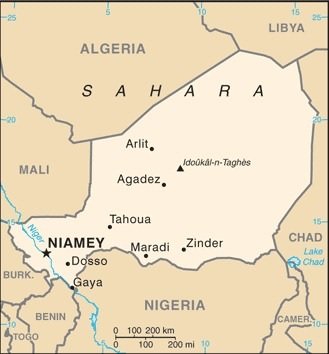

Niger Air Base 201 is located at Agadez. Credit: The World Factbook 2021. Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency, 2021.

On 30 July, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), of which Niger is a member, suspended all commercial and financial transactions between Niger and the other 14 ECOWAS member states, issuing an ultimatum that ECOWAS would "take all measures necessary to restore constitutional order in the Republic of Niger", and demanding Bazoum be reinstated within one week.

The following day, EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen retweeted a message from Josep Borrell Fontales, who serves as High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs and Security and Vice president of the EU Commission, stating the EU's support of the ECOWAS sanctions and urging a return to power of Bazoum.

Defence spending trends during and after war

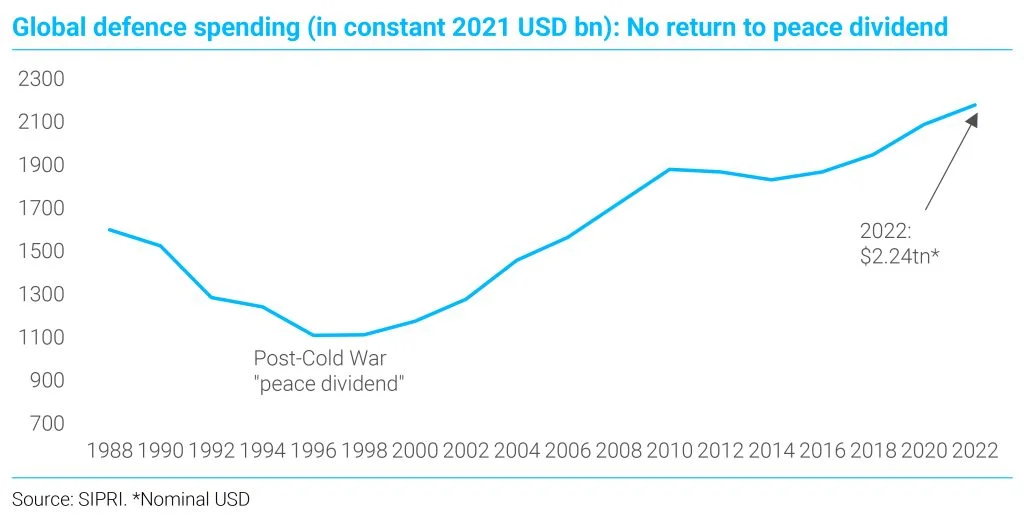

An initial objection would be that wartime surges in defence spending should recede after hostilities end. This ebb and flow of the war tide echoes the underlying driver of geopolitical tensions.

Even if the rise of China challenging the global dominance of the US maintains such tension above the low level which the world enjoyed during the post-Cold War unipolar moment, the Cold War history of détente points to periodic relief. We recently highlighted a potential example in the crucial case of Taiwan, where domestic politics – via next January’s elections – could lower the temperature for a time.

The answer to this point hinges on the war in Ukraine – or rather its aftermath. The spur to rearmament is threat, and the lived experience of threat from Russia after a protracted and bloody war will underpin that spur more reliably even than fluctuating perceptions of the likelihood of war with China.

This is not to make an overly literal argument about ‘forever’ war in Ukraine. Even if, as seems all too plausible, a formal ceasefire or armistice led to some kind of partisan and/or civil war, the small arms combat involved would not in itself move the needle of vast defence budgets.

The key point, instead, is that no plausible outcome of the Ukraine war spells a peace dividend. Even in defeat, nuclear-armed Russia could not be absorbed into the US system after the fashion of America’s vanquished enemies in 1945; and at least until global oil demand finally succumbs to the global energy transition, Russia would have resources for revanche. The resulting armed stand-off – a throwback to the original Cold War in every sense including defence spending – would be sharper still in the opposite case of Russia emerging from the present war with territorial gains.

Depleted inventories drive rearmament investment

The Ukraine war also lies at the heart of the answer to a second, inventory-based objection to this thesis about rearmament as a long-term equity investment theme.

If it were only a matter of rebuilding depleted stockpiles, this objection would have some force. For that done, demand would logically plateau unless live armed conflicts escalate or new ones break out. But eighteen months of fierce combat in Ukraine have delivered a sharper lesson.

The defence industrial base of the US and its military allies has so shrunk since the Cold War as to be unfit for the purpose of supporting high-intensity territorial warfare against peer adversaries. President Biden exposed this reality with remarkable (unintended?) frankness when admitting in a CNN interview on 9 July that “we are running low” on 155mm artillery shells – a combat staple in the Ukrainian theatre.

The US, along with Europe and the rest of its alliance system, now face a political imperative to expand military industrial capacity. This will drive multi-year capital intensive investment.

A designation [of a coup] certainly changes what we would be able to do in the region and partner with the Niger military

– US Pentagon spokesperson.

The war turbo-charges an expensive arms race

This leads to a third and final objection hinging on the question: is the military ‘shopping list’ sufficiently long and weighty to underpin defence sector companies’ structural top-line growth?

The new capacity involved in the plan to quintuple US artillery shell production by 2028 is cheap compared to some of the programmes – such as the F-35 fighter aircraft platform responsible for Lockheed Martin’s latest quarterly earnings uptick – that are regularly in the sights of critics of Pentagon “boondoggles”.

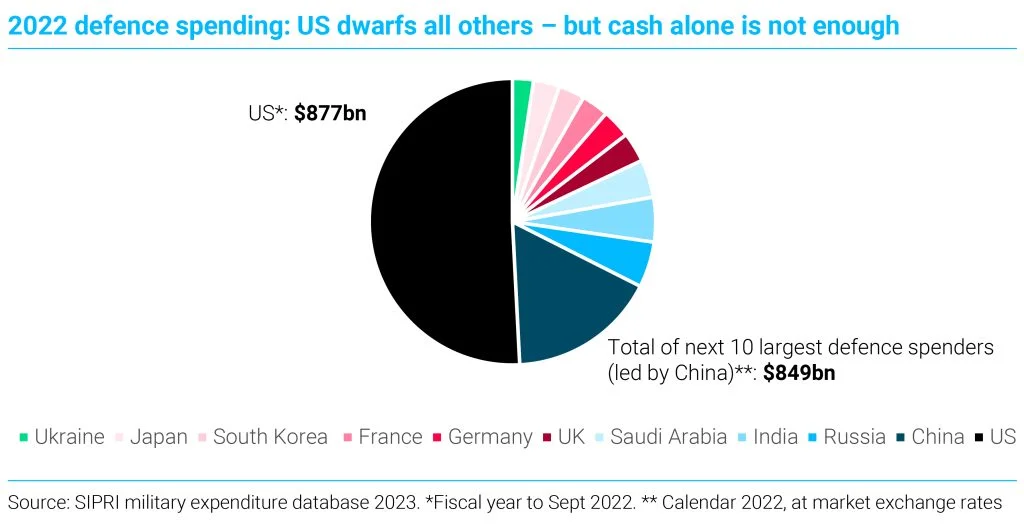

Such critics argue that America’s already preponderant defence spending (see chart below) need not be yet further increased but merely re-directed towards neglected and affordable priorities highlighted by the war in Ukraine.

The answer to this point hinges on the war in Ukraine – or rather its aftermath. The spur to rearmament is threat, and the lived experience of threat from Russia after a protracted and bloody war will underpin that spur more reliably even than fluctuating perceptions of the likelihood of war with China.

This is not to make an overly literal argument about ‘forever’ war in Ukraine. Even if, as seems all too plausible, a formal ceasefire or armistice led to some kind of partisan and/or civil war, the small arms combat involved would not in itself move the needle of vast defence budgets.

The key point, instead, is that no plausible outcome of the Ukraine war spells a peace dividend. Even in defeat, nuclear-armed Russia could not be absorbed into the US system after the fashion of America’s vanquished enemies in 1945; and at least until global oil demand finally succumbs to the global energy transition, Russia would have resources for revanche. The resulting armed stand-off – a throwback to the original Cold War in every sense including defence spending – would be sharper still in the opposite case of Russia emerging from the present war with territorial gains.