Environment

Why prioritising military might over net zero makes no sense

Net zero makes sense from a defence point of view, but the military has historically blocked climate action over operational concerns. Nick Ferris reports.

The Ukraine crisis has shown there is now a strategic argument for net zero from a national security perspective. Yet while militaries have long been innovation pioneers, developing technology that may well be crucial to net-zero innovation, they have themselves historically been laggards when it comes to actually reducing the emissions of their operations. Not only that, armed forces have been blocking the roll-out of offshore wind, a key technology needed to decarbonise the power sector.

“Defence seems years, even decades, behind other sectors such as transport or maritime,” says Christian Eriksen, head of policy and research at think tank the Bellona Foundation.

All sectors – no matter how ‘hard-to-abate’ they are labelled – must be decarbonised to reach net zero, and that includes the military. From fighter jets to lumbering aircraft carriers, the armed forces produce substantial emissions: the estimated 56 million metric tonnes of CO2 the US Department of Defense emits each year is more than the annual emissions of Hungary. In the UK, the Ministry of Defence is responsible for around half of the country’s total public sector emissions.

The low priority given to decarbonising defence is evident in the record of countries’ military emissions submissions to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The framework obliges all states to regularly report their militaries’ emissions each year, but because the reporting is voluntary, there is significant data missing. In addition, the lack of reporting standards means it is hard to know whether the data is reliable or not.

These UNFCCC submissions have been analysed by two NGOs, Concrete Impacts and the Conflict and Environment Observatory (CEOBS), with the results showing that the vast majority of countries either do not divulge their military emissions, or do so but with “very significant underreporting”. The absence of data on military emissions means that pledges made by militaries lack credibility and makes it impossible for the armed forces to be properly involved in international climate negotiations such as those at COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh.

Beyond the climate action apathy that is felt across society, a major reason why the military has not always seen net zero as a priority is that militaries risk their capabilities by adopting new equipment that may prove ineffective.

“The operational requirements of the military [...] mean that if you want to introduce a new fuel or technology you have to be absolutely certain that it works,” explains Björn Nykvist from think tank the Stockholm Environment Institute. “You only need look at the logistical problems faced by Russian soldiers in their invasion of Ukraine to see how important it is to get this right.” These problems included fuel and supply shortages, a lack of convoy protection and a scattered command structure.

However, while challenges around decarbonising more complicated military hardware like fighter planes and battleships remain, the technology to decarbonise other equipment or facilities is already widespread. This could represent a “good first step towards decarbonising the defence sector”, says Eriksen. Although some 60% of US military emissions is from vehicle fuel, much of which might be difficult to abate in the short term, around 25% comes from purchased electricity, which is easier to decarbonise through the roll-out of renewables with battery storage.

It also makes sense for the defence sector to fully align itself with climate action due to the fact that climate change brings massive military risk, both in how it destabilises environments where bases may be situated or equipment held, and how it increases the risk of social or economic change that can trigger conflict.

Opposing offshore wind

However, even as net zero makes sense from a military strategy point of view, the armed forces have historically been a key blocker of new renewables, in particular offshore wind.

“Historically in the UK, the military and the offshore wind industry was not a good mix,” says Alastair Dutton from the Global Wind Energy Council, a former employee of both the Crown Estate and the UK Government working in offshore wind. “At the start, the Ministry of Defence simply said 'no',” Dutton explains. “It was only when we approached the end users – the RAF, navy and army – that we started to make progress”.

Military opposition to offshore wind has typically centered on the tendency of wind turbines to interfere with long-range radar as well as air traffic management systems and low-flying operations.

“Areas reserved for defence training and firing ranges can also cause challenges,” says Dujon Goncalves-Collins, a senior strategic advisor at Vattenfall Wind Power.

“These are all valid concerns over the legitimate risk of wind turbine blades impinging on military operations and training,” says vice-admiral Dennis McGinn from think tank RMI, who was also assistant secretary of the navy for energy, installations and environment in the Obama administration. However, these concerns have – alongside unfavourable clean energy policies – been a key reason why US offshore wind remains so undeveloped in comparison with other markets. As recently as 2020, it was reported that the Pentagon was blocking efforts to develop offshore wind off the California coast, for example.

Military opposition in Europe is just one more contributor to the permitting bottleneck that is at risk of jeopardising Europe’s wind expansion plans, says Christoph Zipf from the European industry group WindEurope. “It is too difficult to get permits for wind farms in Europe, procedures are slow and legal challenges add months of delays,” he says. “Military and civil aviation constraints are among the main barriers, restricting several gigawatts [GW] of wind across Europe.”

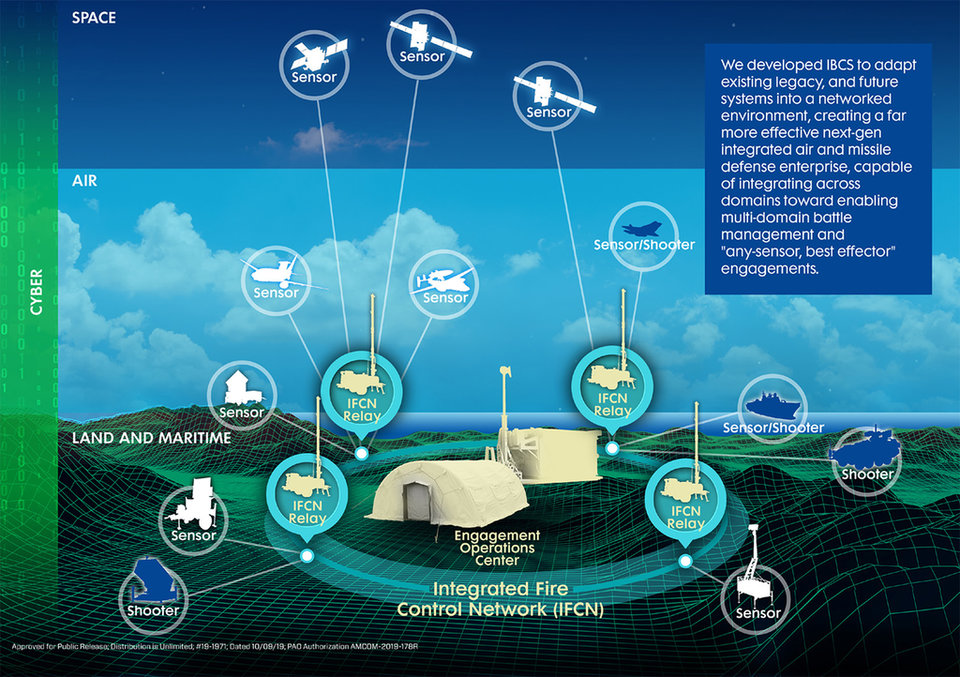

// This infographic shows how Northrop’s Integrated Air and Missile Defence Battle Command System works. Credit: Northrop Grumman

Finding practical solutions

As technology has developed and policy has matured, military opposition to offshore developments has subsided somewhat. In the UK, a joint task force with representatives from the RAF and Offshore Wind Industry Council was established in 2019 to streamline procedures and work through potential points of conflict. A joint strategy was released in September 2021 that details how the organisations are working together to support the deployment of the large wind farms required to meet government offshore wind targets, at that point 40GW by 2030 and at least 75GW by 2050.

Wind farms support the UK’s commitment to be a world leader in clean energy. Because they can potentially impact air traffic control and defence radar, we are working across government and with industry through the Air Defence and Offshore Wind Task Force to deliver mitigating solutions.

Dutton adds that once “dialogue is established”, the “myth” of renewables being incompatible with defence can be dispelled. “With the Ministry of Defence in the UK, we realised that the RAF was simply not being given enough money to upgrade its radar to a system that would not be interfered by turbine blades,” he says. Various actors in the wind industry including the Crown Estate, Equinor, Ørsted and RWE Renewables subsequently clubbed together to pay for the military to upgrade its radar.

“Instead of crude distance rules and no-go zones, we should instead aim for an international, strategic approach [that accommodates different stakeholders and objectives],” says Zipf. “We need proactive and collaborative approaches between governments and wind energy stakeholders.”

In the US, a Department of Defense-run ‘Clearinghouse’ works with industry to promote domestic energy development while ensuring any risks to military capability are minimised. The latter range from the aforementioned interruptions to radar capabilities, to ensuring the military retains space to test missiles, to making sure solar systems do not produce a solar “glare” by reflecting the sun back at members of the armed forces. Originally, the government-run organisation was largely used to approve onshore renewables, but the past two years have seen it facilitate new offshore developments too, says McGinn.

“We are moving in the right direction,” says Vattenfall's Goncalves-Collins. “The military is taking a more active role [in permitting], twinned with its own understanding that it needs to adapt training and operations to a low-carbon future.”

Net zero as a means of defence

The war in Ukraine has shown net zero to be a means of boosting energy security, by encouraging countries to generate their own energy, rather than import hydrocarbons from autocrats – but it has also shown the importance of having a strong military as a means of standing up to global threats. These two issues – defence and net zero – are deeply entwined, and pursuing one without the other makes little sense.

“The fact that energy security is now such a geopolitical issue means that renewable energy infrastructure is going to have to coexist with defence equipment sooner than expected,” says Goncalves-Collins. In practice, this will not only mean the military cooperating with civil authorities in the permitting of new offshore wind but boosting investment in all manner of clean technologies, energy efficiency, hydrogen and e-fuels to decarbonise its own emissions and help bring society to net zero.

“War in Ukraine shows us the importance of having a strong military capability in the US and NATO that we should not sacrifice by decarbonising too rapidly,” warns vice-admiral McGinn. “But it also teaches us that our energy security, economic security and environmental security are all linked, and we need to accelerate the transition to the clean energy economy as quickly as possible.”

// Main image: Illustration of target sharing in Kongsberg’s Integrated Combat Solution. Credit: Kongsberg